May 16, 2019

by Rappler Research Team

This is part of the Rappler Plus paper, “Social Media, Disinformation, and the 2019 Philippine Elections.”

Go to:

The use of digital technologies and social media in Philippine politics and electoral campaigns has changed significantly since this communication medium was first tested by candidates in the 2010 Philippine national and local elections.

Unlike in previous years, a solid media and online campaign strategy is now an indispensable part of the politician’s tool kit. But it is not just extent of use that has changed. The manner by which the medium has been used has also evolved significantly. Unlike in previous years when politicians used it in much the same way they did broadcast media, more candidates in the 2019 elections capitalized on the capacity of the medium to reach and sustain engagement with niche communities, galvanize supporters, and more.

Two key factors contributed to this shift:

- The extent of social media’s reach today

- The medium’s contribution to Rodrigo Duterte’s victory in the 2016 presidential elections.

Contributing factor 1: Reach

While digital media is still not as widely used yet as traditional broadcast media (TV and radio), its reach is wide enough to significantly influence electoral performance. Internet and social media penetration months before the 2019 elections has more than doubled the numbers in 2010.

Estimates on the number of internet and social media users in the Philippines vary.

As of March 2018, or just over a year before the 2019 elections, 42% of Filipinos used the internet, according to a survey conducted by polling firm Social Weather Stations (see graph above). It is important to note that the survey was limited to adults (18 years old and above), and did not cover the total population.1

Digital media research outfit WeAreSocial pegged Philippine internet penetration rate as of January 2019 at 71% of total population (from 46% in January 2016), regardless of age.2 It also pegged the number of active social media users at 71% of the population (from 47% in January 2016). Essentially, this implies that everyone in the country who has access to the internet is on social media.

It is worth noting that the number of users in digital space are not necessarily directly translatable to actual people. There are users who share the same devices while there are also those who have more than one device.

On average, according to WeAreSocial, each Filipino has 10 social media accounts. Analyzing location-based data from Facebook’s audience insight dashboard, Rappler noted that some Philippine cities have more Facebook users than actual population.3 This analysis follows a similar data exploration by WeAreSocial’s Simon Kemp, who noted that there are “more 18-year-old men using Facebook today than there are 18-year-old men living on Earth.”4

Apart from its reach, social media’s power lies in the fact that it allows people to create and post their own content and has the ability to keep people tuned in and engaged – more than traditional media can. For a country like the Philippines, which has a huge migrant population working overseas, Facebook is not just an area where Filipinos get their daily news and information fix from traditional information sources. It also where they stay in touch with friends and relatives abroad.

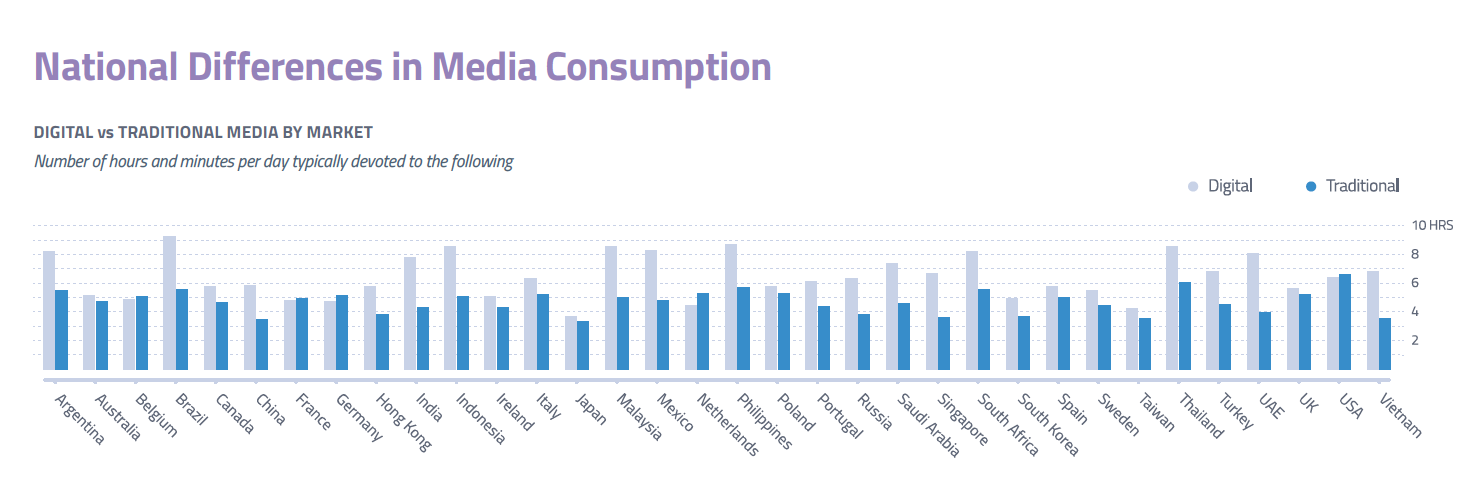

In a 2017 report on Digital vs. Traditional Media Consumption, GlobalWebIndex, a digital research outfit shows how digital outpaces traditional media in countries like the Philippines in terms of number of hours spent. (See graph below)

No updated version of the above report is available. But the number of hours Filipinos spend online continues to grow.

The recent WeAreSocial report (January 2019) ranks Filipinos first globally in terms of time spent online every day (10.02 hours in 2019, up from 9 hours and 38 minutes in 2018) as well as time spent on social media (4.12 hours from 3 hours and 57 minutes in 2018).

Among the various social media channels, the undoubted king, from 2010 up to 2019, remains to be Facebook, according to data from StatCounter.

For this reason, the team decided to focus this research primarily on Facebook data.

Contributing factor 2: Rodrigo Duterte’s 2016 victory

Since US President Barack Obama’s historic win in 2008, aided to a large extent by use of social media, Filipino politicians have routinely included maintaining some form of social media and online presence in their campaign arsenal in succeeding elections. But until 2016, the medium still played a peripheral role in national campaigns.

Even then, it was difficult to ignore. Cynthia Villar, who was a senatorial candidate in 2013 learned this the hard way. She posted better numbers in the pre-election surveys than in the final tally of votes. Villar was initially doing well online, with sentiment analysis showing that positive mentions about her hit an all time high at 551,950 in the first week of March. But this dipped after her “room nurse” comment, which went viral on social media.5 Villar still landed in the winners’ circle but not as well as she probably would have without the social media factor.

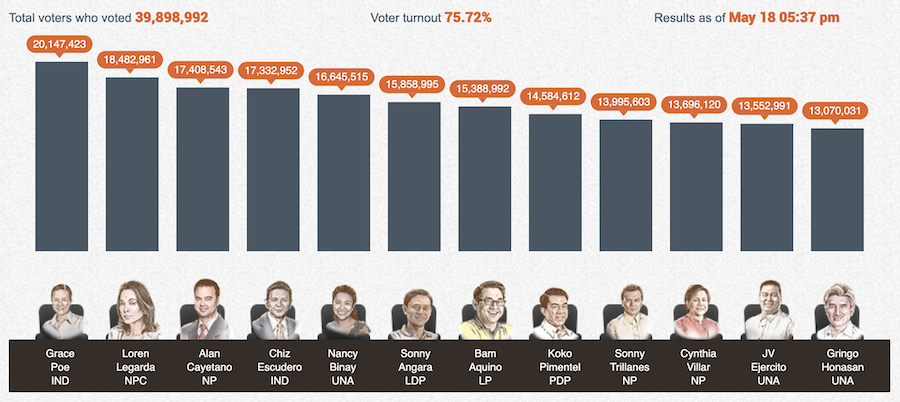

Still, reflecting on the medium’s impact on the 2013 elections, campaign managers of both opposition and administration senatorial teams expressed skepticism over the power of the medium to convert voters.6 It did not help that Grace Poe, who got the most number of votes in 2013 had an insignificant online footprint even though she did say she boosted content on her page on social media.7

From skepticism, attitudes over the power of social media in electoral politics changed in 2016 when the campaign team of acknowledged dark horse Rodrigo Duterte decided to use social media as the primary tool for mobilizing his supporters and generating sustained buzz about him in the presidential race.8

That Duterte’s win was a social media-powered groundswell is very clear. While he also spent a considerable sum on broadcast ads, this was less than amounts spent by his rivals, Mar Roxas and Grace Poe, according to data on campaign spending submitted to the poll body Commission on Elections (Comelec). Ahead of the actual polls the Duterte camp claimed that broadcast giant ABS-CBN refused to air their ads.

Data released by Facebook in March 2016, months before the May presidential elections, showed that Rodrigo “Rody” Duterte was most talked about among presidential candidates. During presidential debates, Duterte went on to win almost every online poll.

Moving into the 2016 elections, numerous Facebook groups and pages were set up to campaign for Duterte. Compared to Duterte’s campaign, the other presidential candidates took on a more conventional approach to campaigning online, focusing on posting and boosting content on their main properties and boosting content.

There were indications that some candidates used bots. In February 2016, for instance, Rappler reported about how its online polls ahead of the elections appeared to have been gamed. From the data analysis, Mar Roxas, who was running against Duterte for the presidential race, appeared to have been the beneficiary of the irregular activity.9

Another study by data scientists at Thinking Machines covering tweets from October 26 to November 5, 2015 noted that about 48% of tweets about Duterte were posted by suspected bots or high-frequency tweeters, versus only 2% to 6% of the tweets about the other candidates.10

The Duterte campaign’s social media manager, Nic Gabunada, however, denied this, saying that what they did was to tap thousands of volunteers.11

To the Duterte campaign’s credit, a significant amount of activity appeared to be organic. As of January 2016, the Duterte camp said it had around 600,000 OFWs who joined 162 “chapters” worldwide all dedicated to Duterte’s campaign and election day mobilization.12 Organized through Facebook groups, many with five- to even six-figure membership counts, these chapters did not just recruit within the ranks of Filipinos overseas, they also influenced their families back home.

Apart from the use of numerous groups and pages that targeted niche communities, however, the Duterte campaign was also not shy to use negative campaigning, creating false content, and amplifying existing negative material against their rivals.13

Beyond the black propaganda, online supporters of Duterte also functioned as defenders of their candidate. In a number of occasions, they took this vigilance to extremes.

One specific example of this was when the former Davao City mayor’s supporters created a number of Facebook pages to attack a student who was perceived to have been rude to their candidate in one of the many fora organized ahead of the elections. Some of these pages went as far as saying that the student should die. Some released his phone numbers and other personal details on social media.14

These behaviors, initially displayed during the 2016 elections, continued beyond the elections as critics of his brutal war on drugs became primary targets of systematic and weaponized online attacks. Individual journalists, news groups, and opposition politicians were tagged as enemies of the administration and were depicted as obstacles to Duterte’s reform efforts.

-----

1 4th Quarter 2017 and 1st Quarter 2018 Social Weather Surveys: 67% of Pinoy internet users say there is a serious problem of fake news in the internet, Social Weather Stations, June 11, 2018, https://www.sws.org.ph/swsmain/artcldisppage/?artcsyscode=ART-20180611190510

2 Digital 2019, WeAreSocial, https://wearesocial.com/global-digital-report-2019

3 Vernise Tantuco, “Did you know that some PH cities have more Facebook users than actual population?” Rappler, October 26, 2018, https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/215159-list-philippines-cities-more-facebook-users-than-population

4 Simon Kemp, “Startling truths about Facebook,” August 22, 2017, WeAreSocial UK Blog, https://wearesocial.com/uk/blog/2017/08/startling-truths-about-facebook

5 Maria Ressa and Michael Josh Villanueva, “Social media sentiment analysis of 2013 senatorial candidates,” Rappler, May 9, 2013, https://www.rappler.com/nation/politics/elections-2013/28534-social-media-sentiment-analysis-2013-senatorial-candidates

6 Carmela Fonbuena, “Social media dominance over TV means better PH elections,” Rappler, April 24, 2013, https://www.rappler.com/nation/37189-social-media-dominance-means-better-philippines-elections

7 Grace Poe at #ThinkPH: Winning the 2013 elections, Rappler, August 25, 2013, https://www.rappler.com/move-ph/37204-thinkph

8, 11, 13 Jodesz Gavilan, “Duterte’s P10M social media campaign: Organic, volunteer-driven,” Rappler, June 1, 2016, https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/rich-media/134979-rodrigo-duterte-social-media-campaign-nic-gabunada

9 “Who gamed the Rappler election poll?” Rappler, February 26, 2016, https://www.rappler.com/nation/122060-manipulate-game-rappler-election-poll

10 Thinking Machines Data Science, “KathNiel, Twitter bots, polls: Quality, not just buzz,” Rappler, April 1, 2016, https://www.rappler.com/technology/social-media/127920-kathniel-twitter-bots-elections-quality-buzz

12 Pia Ranada, “Over 600,000 OFWs mobilizing for Duterte campaign,” Rappler, January 30, 2016, https://www.rappler.com/nation/politics/elections/2016/120572-overseas-filipino-workers-support-rodrigo-duterte

14 “Duterte to supporters: Be civil, intelligent, decent, compassionate,” Rappler, March 13, 2016, https://www.rappler.com/nation/politics/elections/2016/125701-duterte-supporters-death-threats-uplb-student